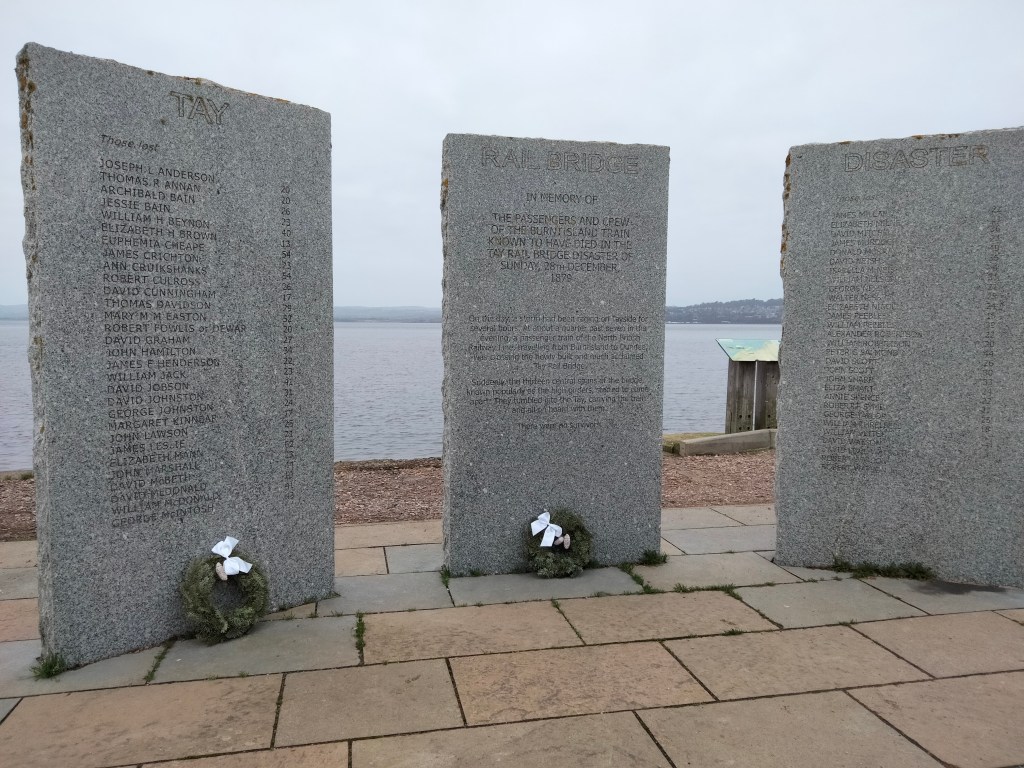

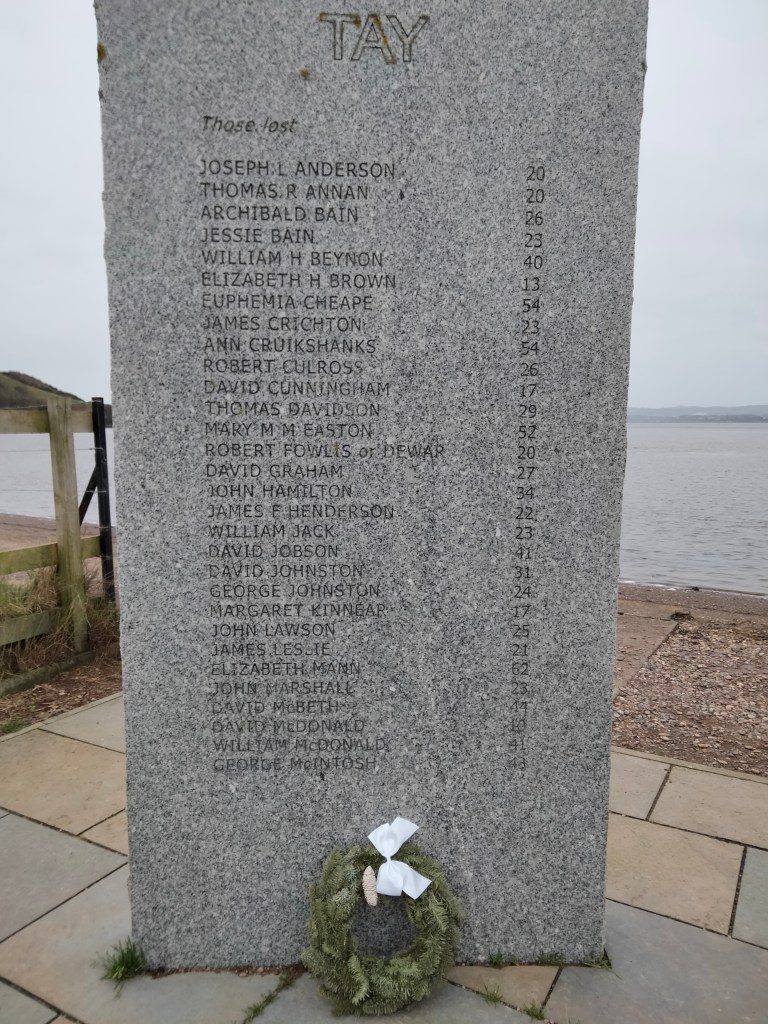

On Saturday the 28th December 2013, at simple but moving ceremonies held on both sides of the Tay, memorials were unveiled to the 59 known victims of the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879.The great majority of those who were lost came from Fife and Tayside, and typically were returning to Dundee on the train after visiting family and friends on the south side of the river. This was the 134th anniversary of the tragedy, an event still powerfully remembered in the locality, and now marked in the form of substantial granite panels bearing the names of all those passengers and crew who went down with the train.

The memorials were erected through the auspices of the Tay Rail Bridge Disaster Memorial Trust, who wish to thank all those charitable organisations, businesses and individual citizens without whose support the enterprise could not have succeeded.

Every year, on the anniversay of the disaster, I undertake make my annual ‘Wormit pilgrimage’ to lay 2 small wreaths (see 2 pictures above) at the memorial. The first picture shows a wreath for all the victims. The second picture shows a wreath at the left stone for Margaret Kinnear (17) who was related to someone I know.

Sir Thomas Bouch’s grave

The last victim of the Tay Bridge disaster was the designer of the bridge Sir Thomas Bouch. After the Court of Inquiry report was published (June 1880), which principally blamed him, he died on the 30th of October 1880 of a ‘broken heart.’

The Builder’s (6 Nov 1880) obituary was in the much favoured flowery prose of the time. To quote a section:

Those of our readers who have taken an interest in the circumstances attending the destruction of the Tay Bridge, which have been so frequently referred to in our columns, must have read the announcement of the death of Sir Thomas Bouch with a feeling of melancholy regret. Whatever view may have been taken with regard to the amount of personal responsibility which rested upon the engineer in relation to the calamity of last December, the sorrowful ending of so successful a career carries the mind beyond the range of technical fault-finding, and ought to lead us to contemplate rather the bright than the dark side of a life that has terminated so sadly.

Any one who saw the late Sir Thomas Bouch moving to and fro during the inquiry into the disaster with which his name must forever be associated, could not help seeing that he was a stricken man. The tear and wear of his professional life, mixed up as it had been for many years with ventures in which he had a deep pecuniary interest, had already begun to tell their tale.

When, in addition to all this, he suddenly found himself thrust out of the position of trust and responsibility which his abilities had rendered apparently secure, and placed in an attitude of defence towards the work of his own intellect, and the anxious labour of years, the strain that was thrown on his constitution could be read by the passer-by.

The circumstances, in the mere aspect of their human interest and as a commentary on the vanity of human affairs, appear to us to afford the materials for a tragedy, the motive of which is peculiar to the times we live in. In the climax, when the fates have come with the shears, the end, instead of being a culmination of the sorrow, is rather of the nature of a kindly remedy for evils that could not longer be borne.

The Institute of Civil Engineers obituary was more critical of Bouch remarking that “In his death the profession has to lament one who, though perhaps carrying his

works nearer to the margin of safety than many others would have done, displayed boldness, originality and resource in a high degree, and bore a distinguished part in the later development of the railway system.”